By Noemí Riudor

Joan Garcia Rabascall was born in Lleida on 11th December 1900. He was the youngest of four brothers. His father was Francesc Garcia Boronat and his mother was Carme Rabascall Martí, both were been born in Cornudella (Tarragona). When Joan was so young, he began to work in the Public Works department of the Generalitat of Catalonia because he had a brother working there.

Regarding his political thinking, he was a republican person. He was related with Esquerra Republicana circles in Lleida. He and his friends were linked to a group called “La Petera” it was a political group and perhaps ludic too. Joan didn’t go to the Spanish Civil War and when it finished he was disqualify from being a public official and he had to work for several insurance agents as an autonomous worker.

On 21st November 1941 he married Dolors Solà Alberich. On 16th August 1946 they had their only daughter, M. Carme Garcia Solà.

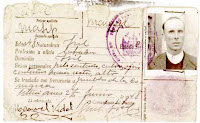

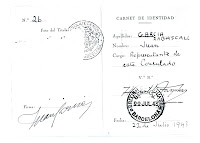

Concerning with his job for the British Consulate in Barcelona, we have a little information. We have a document forward for the Consulate on 4th July 1943 where we can read he was the person designated for the Consulate to do the administrative tasks related with the British subjects who were in Lérida or Huesca provinces. Joan Garcia had an identity card (22nd July 1943) as a representative of the British Consulate of Barcelona.

In the book Paso clandestino. Las otras listas (2004), by Alberto Poveda, Joan Garcia apperared as a representative of the British Consulate in Lleida town:

“El Consulado general británico en Barcelona designó como representante para las relaciones con el Gobierno Civil a Juan Garcia (…) Era también joven, resuelto, eficaz. Fue precisamente el coautor de una solución de alivio para los refugiados, para sus «canadienses», con efecto sobre los demás: un balneario.” (POVEDA 2004, 167)

Alberto Poveda Longo was a young man from Madrid who was studied journalism. He sat an examination for the Ministry of the Interior and he was sent to the Civil Government in Lleida where he arrived in September 1942, he was 27 years old. In Lleida, his work consisted in took care of the refugiees who arrived in the Lérida province; Poveda spoke French and a bit of English.

One day Joan Garcia Rabascall went to the Civil Government in Lleida to get an appointment with Poveda. Garcia presented himself as the consular agent who was in charge of the British and Canadian citizen imprisoned in the Seminari Vell (Lleida). Since this moment, Garcia sent to the Civil Government several documents to require the freedom of British and Canadian people imprisoned in Lleida. The British Consulate in Barcelona took charge of their maintenance and transfer to Barcelona.

Joan Garcia had a good appearance, he was a tall and elegant man with polite manners. Poveda thought he was educated in a British environment. But Garcia never went to the Great Britain and in according with his niece Joana Garcia Sisteré, he learned a bit of English in 1943, thanks to an English teacher (probably payed for the Consulate) who went to his home to give him some lessons.

Sometimes, Poveda and Garcia met in the Palace Hotel in Lleida. This place was one of the hotels where the British Consulate lodged refugees. The way that Joan Garcia stayed at the hotel, confused Poveda who thought Garcia was lodged there. Perhaps Joan Garcia needed to be unnoticed.

Because of the interest of Joan Garcia and other consular agents to freedom the refugees imprisoned in the Seminari Vell, and because of the increasing number of people took prisoner there, the authorities of the Civil Government had to search a solution to reduce the boarders’ number in the prison. So that, on 7th May 1943, Joan Garcia could release a group of 70 people which were moved to the Rocallaura health resort (POVEDA 2004, 180-181). Since this moment, Rocallaura became a place where the refugees of several nationalities waited for their departure from Spain. The British Consulate paid the lodging and maintenance expenses, and the person in charge of the payment was Joan Garcia. Thanks to a document guarded in the Historical Archive of Lleida Province (provided by Josep Calvet) we know that the British Consulate assumed the lodging and maintenance expenses of the British foreigners. This document was written by Garcia on 15th December 1943; Garcia informed to the owner of an unknown hotel about a bill payment. The British Consulate paid the amount of 2,150 pesetas as lodging and maintenance of John Gordon Covington and his family, Bob Tibbatts and Freddy Duncan.

The appointments between Poveda and Garcia, since the middle of 1943, were less frequents than before. Perhaps liberate the prisoners was easier since the moment when the Spanish authorities allowed their lodging in Rocallaura. At any rate, Poveda thinks that between 1943 and 1944 the networks members in Catalonia were able to create a direct way between the Pyrenees and Barcelona, so that there were minus aircrews imprisoned in the Seminari Vell. During 1944, Poveda and Garcia didn’t meet more.

On 6th April 1944 a Halifax bomber of 644 Squadron RAF based on Tarrant Rushton in Dorset, took of. A few hours after, the plane was shot down by the Germans near Cognac. One of the six Halifax crews died, another one was captured and the other four succeeded in escape but not together. John Franklin fell near Ray Hindle and thanks to the Pat O’Leary evasion network, the two crews arrived to Spain crossing the border above the Pont de Rei, on 4th May 1944 (GOODALL 2005, 33-38). They were arrested in Vielha and moved to the Seminari Vell prison in Lleida.

On 20th July 2006, John Franklin recognized Joan Garcia in a photo. Garcia was the representative of the British Consulate who liberated him twice. The first time, Franklin and Hindle, were liberated following the regular procedure. First, the consular representatives must to identify, inside the prison, the British subjects. Then they must to notify to the Civil Government the name of the British people to liberate and guarantee their lodgement and maintenance in a hotel of the city before they move to Barcelona.

The two English mates, during their last journey stage between France and Catalonia, had met an American aircrew named John Betolatti. The stay in a hotel in Lleida was, for the three young men, a little holiday after the last months running away through the occupied France.

The refugees liberated from the Seminari Vell prison were lodged in several hotels in Lleida. They were on probation and they had to respect the curfew rules. Alberto Poveda says in his book that the foreigners shouldn’t have been in the street from 9 p.m. but during the summer they could be in the street until 11 p.m. (POVEDA 2004, 172-173).

In spite of the curfew rules, on day the three friends decided to visit the local cinema. When the film had finished, a couple of civil guard were waiting for them to move the three young men to the prison again: “three of us having broken the curfew rules from the hotel to visit the local cinema. We were escorted to jail through the main street, I thought with some satisfaction by the civil guard” (mail from John Frederick Franklin, 20th July 2006)

John Franklin, Ray Hindle and John Betolatti were in prison again but thanks to Joan Garcia they were liberated: “with the small stone cell and the tiny grill window we were released with your grandfather in the background. You can imagine our relief next morning” (mail from John Frederick Franklin, 20th July 2006).

About the time while Joan Garcia Rabascall was working for the British Consulate, I know some unconnected family stories. His daughter M. Carme Garcia Solà remembered a story about an evader who was a prince; Joan Garcia had bought him some coins of gold because the aristocrat needed more money than the allowance given by the Consulate to every refugee. She also remembered a situation happened in the Palace Hotel in Lleida when a couple of German police came in to inspect. Joan Garcia had to face up to the refugees complaints; surely they been frightened with these unexpected visitors. Garcia only could say to them: “in this country is more legal the presence of these Germans that the British Consulate activities”. Poveda also describes in his book this situation:

“Cierto día, visitaron al nuevo Gobernador Civil dos oficiales alemanes de la guardia fronteriza, perfectamente uniformados, altos, fuertes y con aire de arrogancia. No supe nada relacionado con el propósito de la visita y pensé que se trataba de una cortesía protocolaria hacia la autoridad española vecina.

Horas más tarde, cuando me dirigía a la oficina de Correos, los vi salir del Hotel Palacio, zona muy céntrica de la ciudad y, consiguientemente, algún refugiado tuvo que advertir su presencia y comunicarlo rápidamente a otros. Así ocurrió, sin duda, pues cuando regresaba de mi gestión por el mismo camino, cuatro refugiados se me acercaron con muestras de nerviosismo y me preguntaron qué peligro podría representar aquella visita. Les tranquilicé diciendo que, en todo caso, no se vería alterado el statu quo establecido y del que se derivaba su situación de libertad. La inquietud se me manifestó en otro encuentro a continuación.” (POVEDA 2004, 174).

M. Carme Garcia remembered his father talking about once when he took care of Alexander Fleming’s wife. The last family story we have is perhaps the more distressed. Joan Garcia was inside a car with a Consular official when they were shot. We think there weren’t any dead person in this attempt.

Joan Garcia had a nightmare repeatedly during his life. He dreamed somebody was persecuting him and he shouted demanding help. When he woke up he said he didn’t remember anything. Maybe this nightmare hasn’t any relation with the situation in the car but these are some details about the troubles lived during these hard years.

Joan Garcia Rabascall died in Lleida on 5th January 1985. He was 84 years old.

Some Consular representatives and Red Cross representatives in charge of the refugees in Lleida during the Second World War:

Garcia Rabascall, Joan. British Consulate in Barcelona. Documentation of Family Riudor-Ros / (POVEDA 2004, 167, 180-181) / Documentation of the Arxiu Històric Provincial provided by Josep Calvet.

Tous Gironès, Josep. Dutch Consulate. Documentation of the Arxiu Històric Provincial provided by Josep Calvet.

Revelly, Yves. International Red Cross. French delegation. (POVEDA 2004, 111).

Scherer, Marc. French Red Cross. (POVEDA 2004, 114).

Reyes, Alicia. Belgian Consulate in Barcelona. (POVEDA 2004, 162).

García, Roberto. American Consulate in Barcelona. (POVEDA 2004, 166).

Gomand, Norbert. Luxembourg Red Cross. (POVEDA 2004, 167).

Bibliography:GOODALL 2005

GOODALL, Scott, The Freedom Trail, Inchmere Design, 2005.

POVEDA 2004

POVEDA LONGO, Alberto, Paso clandestino. Las otras listas, Ed. Alberto Poveda Longo, Madrid, 2004.

From November 22th 2007 to January 31th 2008

From November 22th 2007 to January 31th 2008